We are thrilled to present a new review by Nick Mastrini for EUNIC London. The New European Documentary series continued with a screening of Lithuanian film ‘Barzakh’ at Picturehouse Central, followed by a Q&A with director Mantas Kvedaravicius.

‘Barzakh’, the title of Mantas Kvadaravicius’s documentary set in a Chechen city, is a word which refers to a region between the living and the dead. This place of purgatory, or limbo, represents the film’s focus: the disappearance of the friends and family of the Chechen people — a human rights issue that Kvedaravicius explores poetically and intimately.

Rather than explicitly attacking those who oppress the Chechen people, the director lays bare the reality of life in Chechnya, where some are recovering from past atrocities and others must also deal with the difficulties of the present. These difficulties include not only the complex relationship between Chechnya and Russia, but the rule of Ramzan Kadyrov, which was ‘acquiring power’ within the Republic during Kvedaravicius’ time there.

The director’s interest is in the human, quotidian aspect of this ordeal — the way in which any individual, and the community, responds. He begins his Q&A by explaining his route into film-making via his study of anthropology:

‘I was doing my field work. Cinema can speak to … the sense of abnormality [in Chechnya]. The world there seems very normal, but it’s not. This discrepancy is what I tried to capture.’

This discrepancy between the normal and abnormal is encapsulated by the title ‘Barzakh’, and emphasized by the abstract images shown when Kvedaravicius cuts away from his interviews with Chechen residents. Shots underwater in a nearby lake (Mantas also notes that he is an underwater archaeologist) move eerily, depicting a haze of clouds and particles, bringing the viewer into their own state of limbo. We learn in the Q&A that this lake in particular has further meaning: Kvedaravicius was told that ‘they dump bodies from helicopters there’.

Image via triplenode.com

Along with the shot of the lake, Kvedaravicius adds blurry cinematography, providing a dreamlike quality to images of rain-swept dirt tracks and women in prayer. This beautifully reflects the fact that ‘Barzakh’ is illusory, only dreamt as a place of hope by the individuals that are without someone who has disappeared.

Only in dreams can they recover their loved ones — in reality, it is impossible to know whether they are dead or alive. However, as Mantas states, ‘how can you say a dream is wrong? It is there, boom.’ Believing in the return of those missing is enough, as is shown by one clairvoyant woman, with close-ups showing her manipulating objects in her hands, finding meaning in what she can hold rather than only dream of.

Kvedaravicius visited Chechnya in the decade following the end of the Second Chechen War, and experienced a world trying to move beyond its tumultuous past. ‘All the signs of war were being eradicated’, he says, and those in power tried ‘to make the city look as normal.’ But he notes the ‘trauma was heavier than the space itself spoke about’, suggesting a separation between the true feelings of those he interviews and the society that was being amended around them.

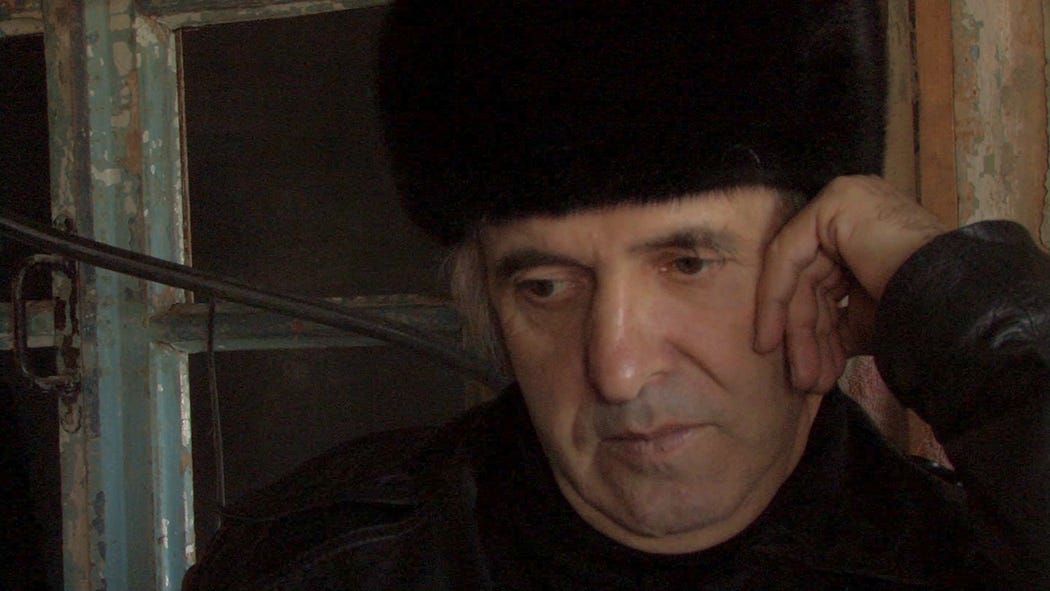

One interviewee, a man whose ear was cut off but survived ‘nineteen attempts on his life’, provides a stark account of the conflict’s events, explaining the use of a school for deaf children when torturing Chechen individuals. Meanwhile, a family waits silently for the return of a son, dealing with documents and dread but unable to do anything more. Kvedaravicius presents us with these snapshots of the reality of geo-political conflict — a powerful reminder, when viewing Barzakh in London, of the struggle of day-to-day life elsewhere.

Barzakh, as with other documentaries within this series, unveils a slice of life that is unheard of in the UK, where the mass media tends to ignore subjects such as this, in favour of more accessible news.

The situation in Chechnya isn’t ‘news’ anymore — at least, it isn’t the type of story reported in order to increase readership and viewership. It is a long-standing issue, and Kvedaravicius has created an intriguing film to address the ongoing problem.

Nick Mastrini writes for SAVAGE Magazine and Within and Without.

Nick Mastrini writes for SAVAGE Magazine and Within and Without.

Find Nick on Twitter

This article was originally posted on Within and Without

This screening of ‘Barzakh’ was supported by the Lithuanian Cultural Institute.

The New European Documentary series continues with a screening of Italian film N-Capace, a true story of grief, nostalgia and destruction. A Q&A will follow the screening.