Picture: Rob Stothard/Getty Images

You might ask yourself what retail therapy, Madame de Pompadour and a digital Harlequin have in common? They are all ingredients of the V&A beautiful and newly re-opened EUROPE 1600-1815 Galleries. The new galleries open at a time when the concept of Europe in Britain is politically and culturally contested. The time has never been better, then, to ask What was Europe?

We’ve asked Lesley Miller, Lead Curator of the Galleries to give us an insight into the art and design of 17th and 18th-century Europe, the challenges of the curation process and to tell us about her favourite pieces in the collection.

Get ready to go back in time and to enjoy a guided tour of European culture with its best guide in town.

Lesley, you are the Lead curator of the freshly re-opened Europe 1600-1815 Galleries, which are quite a spectacular display of the richness but also of the complexity of European culture at that time. What are the vision and messages behind the Galleries and what will the curious and adventurous learn from visiting them?

As you say the new galleries devoted to the art and design of 17th and 18th-century opened just recently, last December to be precise, after a major five-year renovation project. The displays aim to engage and enthuse twenty-first-century audiences, some of whom may have little or no knowledge of European history and to whom many of the particularly grand objects may be quite alien. Fortunately, the recent international commemorations of the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo will have reminded visitors of the significance of our end-date – the death knell for French political and economic dominance in Europe and the fanfare for Britain’s assumption of power, with Prussia and Russia in the ascendant. Culturally and aesthetically, France was, of course, to continue to share her savoir-faire and savoir-

The unfolding story in the galleries relays three key messages about this period: first, that, for the first time ever, Europeans systematically explored, exploited and collected resources from Africa, Asia and the Americas for art and design; second, that France took over from Italy as the undisputed leader of fashionable art and design; and finally, that ways of living came to resemble those we know today, a much broader spectrum of society having access to little luxuries that had previously only been purchased or enjoyed by the wealthy and powerful. These messages are relayed through about 1100 objects from the Museum’s own collections in displays that focus predominantly on the arts of living, rather than on specific historical events.

These Galleries were fully refurbished, curated and freshened up indeed. When did they first open and how do they fit into the rest of the Museum’s narrative?

The Europe Galleries continue a narrative begun in the ‘Medieval and Renaissance Galleries 300-1600’ on the opposite side of the Museum’s Grand Entrance and complement that of the ‘British Galleries 1500-1900’ on the two floors directly above. Designed by Sir Aston Webb, they first opened in 1909, became the home of ‘Continental European art and design, 1525-1825’ in 1951, and were last fully renovated in 1972 – at a time when museum visitors’ knowledge and expectations were very different from now.

In line with current Museum policy the spaces have been returned to their original glory, in this case by the architectural practice ZMMA, who also designed – in a thoroughly modern idiom – all fixtures, fittings, plinths and cases to meet current conservation, access and security requirements. The ceilings are lofty, allowing the effective display of very large objects such as tapestries. The windows are visible, thus enabling visitors to orientate their position relative to the outside world – though they are shuttered to prevent the entry of light that would damage the historical artefacts.

The selection of themes and methods of interpretation for the displays are intended to promote knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of the designed world, the physical displays being part of a much wider programme that brings the V&A into people’s lives through a range of activities within the Museum and digital content offered via the Museum’s internet site.

Re-staging an era in its artistic, social and economic context is a complex endeavour. What were your main challenges and concerns when curating the collection of the Galleries with your team?

In a design museum such as the V&A, any history of art and design of any period will always be partial, dependent on accidents of survival, generations of museum collecting policies, and the mission to appeal to a wide range of audiences. Inevitably, the story reflects elite culture rather than offering a comprehensive overview of European society. The team was aware of these limitations as it worked through ideas for themes and through the collections to see what was available.

Our major concerns at the beginning were how to define Europe. We were keen to avoid previous emphasis on Western Europe, and to extend our remit from Portugal in the west to Russia in the east, from Spain in the south to Sweden in the north, and to highlight interconnections with the rest of the world, making sure not to omit the unpalatable truths of war or the slave trade. Our collections, however, assembled over the last 150 years or so, have certain strengths and weaknesses.

There are virtually no architectural pieces, few central or eastern European objects, surprisingly few from Scandinavia or the Baltic states, or from Ottoman Europe. There are few non-luxury objects, despite the growth of a ‘middling’ market in precisely this period in most parts of Europe, and there is a heavy bias towards French material. While we debated including British objects in our displays, we chose largely to exclude them in order to give space for our continental European collections to shine. This was a practical rather than political decision, as the V&A already displays the national collection of British decorative arts and design in the British Galleries, exploring their characteristics and development in some detail.

Let’s pretend we can all beam up to the V&A right now Lesley, can you give us a virtual guided tour of the Galleries and what we visitors and flaneurs will find there?

The layout of the galleries paces the content for visitors, making sure they do not suffer from that well-known condition ‘museum fatigue’. Four long galleries are punctuated by three smaller ones – and there is plenty of seating.

The long galleries carry the chronology: ‘Europe and the World, 1600-1720’; ‘The Rise of France, 1660-1720’; ‘City and Commerce, 1720-1780’; and ‘Luxury, Liberty and Power, 1760-1815’. Each is characterised by a certain style – what was then the ‘modern’ style and what art historians now label as ‘Baroque’, ‘French Baroque’, ‘Rococo’ and ‘Neoclassicism’. The bold colours of the walls in each gallery emphasize changes in taste. From papal purple to light stone grey, these 21st-century colours conjure up an impression of the grandeur or elegance of the time.

The smaller galleries punctuate this chronology and offer a more immersive experience, including different activities in which visitors may actively participate: a bronze activity table for families in the Cabinet allows the exploration of 17th-century collecting through drawing and brass rubbing, riddles and a board game; a modern installation (the Globe) encourages discussion and reflection in the Salon; and an interactive film in the Masquerade, set in mid-18th-century Venice, reveals social interactions at a ball, in a gambling house and in a piazza – and much laughter is already issuing from this space as visitors try to imitate the actions of the character of Harlequin.

Well that feels as if we were just there with you! Can you give us your special selection of 4 of the most iconic pieces of the collection?

Several objects in displays in our gallery ‘City and Commerce, 1720-80’ are suggestive of our desire to reveal not only French taste, but also the excellence of production in other parts of Europe’.

In the first display explaining the formal qualities of the Rococo style, initially championed in Paris but later extending to all corners of Europe, hangs a masterpiece by the French court artist François Boucher.

It is a portrait of Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV’s mistress and companion for about 20 years before her death in 1764. She is portrayed informally dressed in plain silk and pearls, reading in a garden setting. Several large tomes beside her suggest her intellectual aspirations. Our challenge was to decide where to locate her in this gallery as she was such an important leader of fashion, patron of the arts, and also involved in the intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment. She deserves a display of her own, but we did not have enough objects that could be definitively associated with her or attributed to her patronage. We chose therefore to hang her in a prominent position beckoning visitors into the Rococo display (indicating her taste) , while she looks out to the Salon, our Enlightenment gallery (indicating her ideas).

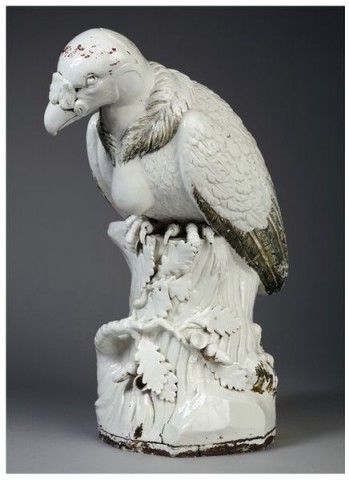

In the adjacent display ‘City Workshops’, manufacturing strengths and specialisms in different European cities, not just in Paris, are revealed. A porcelain vulture is a dramatic reminder that the Meissen factory in Dresden was first in Europe to copy successfully Chinese porcelain processes, and that Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland was a great lover of this material. Indeed, the vulture was one of 600 life-size animal sculptures he commissioned in 1730 for his porcelain menagerie in one of the Dresden palaces.

In contrast, a cut steel fireplace from the Imperial Armaments Factory at Tula near Moscow, an enterprise much patronised by the Catherine the Great of Russia, offers an insight into the fashionable production of ‘the Birmingham of Russia’. While the steel originated in Sweden, both the construction and decoration represent a merging of Russian and British influences that exemplifies the relationship between the two countries at the end of the 18th century.

In the final display ‘Luxury Shopping’ we focus on the rise of ‘retail therapy’ in the faubourg Saint Honoré in Paris, today still a luxury zone par excellence, demonstrating how prestigious retailers combined different objects from different places into fashionable items for the homes of the wealthy. Here Chinese fish vases are mounted in Paris-made gilded wood stands featuring scrolls, bulrushes and shells. Adapted in this way, they would have harmonised with an exuberant Rococo interior.

In brief, the V&A’s 17th and 18th-century Europe is a continent in which fine craftsmanship and manufacturing ingenuity, comfortable living and pleasurable pursuits for increasing numbers of people thrived, sadly often fed by warfare and exploitation.

Find Marie on Twitter: @Marie_Proffit

To mark the opening of the new galleries, the V&A has published The Arts of Living: Europe 1600-1815, edited by Elizabeth Miller and Hilary Young, two of the project’s curators. For further details of the process behind creating the galleries, see Dawn Hoskin’s blog.

Europe 1600-1815 Galleries, V&A Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 2RL. T: +44 (0)20 7942 2000, www.vam.ac.uk. Opening hours : 10.00-17.45 daily.

Lesley Miller has since 2005 been a Senior Curator in the Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department at the V&A. She was Lead Curator for the Europe 1600-1815 Galleries project at the V&A between 2010 and 2015, and since 2013 has also held the post of Professor of Dress and Textile History at the University of Glasgow.

Fig. 1 Gallery 3 ‘City and Commerce, 1720-90’

Fig. 2 Madame de Pompadour by François Boucher. Made in Paris, France, 1758. John Jones Bequest. Museum no. 487-1882.

Fig. 3 King Vulture Made at the Meissen factory, Dresden, Germany in about 1731. Modelled by Johann Joachim Kändler. Porcelain. Purchased with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund and the Friends of the V&A. Museum no. C.11-2003.

Fig. 4 Fireplace Made at the Imperial Armaments Factory at Tula, Moscow, Russia, about 1800. Steel. Museum no. M.49-1953

Fig. 5 Fish vases Porcelain made in China (Jingdezhen); gilded mounts in Paris, France, 1725-50. Given by Lady Bonham-Carter. Museum no. FE.34, 35-1970.