Virtually nothing now can be said about Johann Sebastian Bach that is free of cliché. If someone (especially someone who is actually a lover of classical music) says ‘I’m not really into Bach’, the reaction from other music-lovers tends to be one of incredulity. It’s like saying ‘I’m not really into oxygen’. This bewigged provincial organist of the early 18th century Germany was a creative, formative genius who can be said to be the sacred heart of western classical music – and, indeed, of other not-so-classical music. Jazz musicians can work wonders with him too. Bach is possibly the most immune to whatever performers or improvisers do to his music: it survives, unassailable, intact, impervious to the best and worst of human engagement with it. When I was a schoolboy a friend and I used to try to play some of the Two-part Inventions on flute and trombone. It must have sounded crazy, but still a little bit wonderful.

The great Spanish cellist, Pablo Casals, put it more elegantly than most:

To strip human nature until its divine attributes are made clear, to inform ordinary activities with spiritual fervour, to give wings of eternity to that which is most ephemeral; to make divine things human and human things divine; such is Bach, the greatest and purest moment in music of all time. [1]

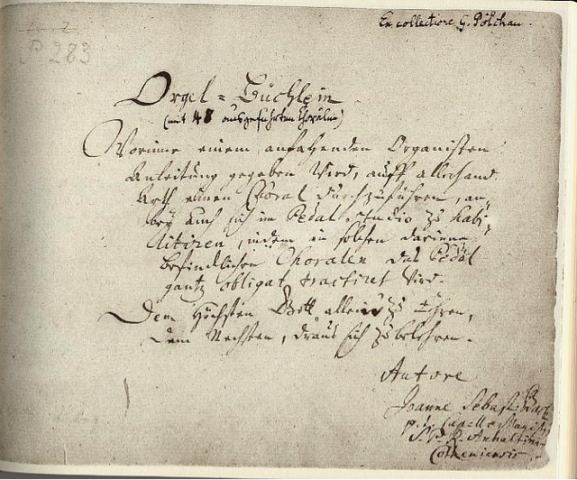

Part of the wonder of Bach’s output is its range, its versatility – there is everything from the monumental (the Passions, the B minor Mass) to the tiniest of keyboard pieces. It’s towards this latter extreme that we find the tantalising Orgelbüchlein – the Little Organ Book.

The Orgelbüchlein is a collection of ‘chorale preludes’, organ pieces based on Lutheran chorales arranged across the chronology of the whole liturgical year. Maybe that should say ‘destined to be set’: because of the 164 titles, Bach only completed 46, with a fragmentary sketch of one more (amounting to fully two bars).

What he did write were miniatures, though not remotely small in their imagination, rigour and virtuosic demands. All last between two and five minutes, mostly nearer the former than the latter length. Then there are sheets and sheets like this:

The title here is Wenn mein Stündlein vorhanden ist (‘If the hour of my death is at hand’), and is from the Lutheran Hymnal. The original chorale was by one Nikolaus Herman. In Bach’s little book, this is in the ‘Death and the Grave’ section.

Until now these tabulae rasae have been left as they are, as though to ‘complete’ Bach’s work would amount to a sort of counter-factual sacrilege. But finally someone dared to suggest something like this, and the Orgelbüchlein Project began.

That someone is William Whitehead, an English organist of international note. He heard the plaintive cries of ‘those 118 ghosts’ (as he calls them – the titled-but-blank pages) and decided to give them bodies, give them life.

This began way back in 2007 as a collaborative exercise between the organ and composition departments at Trinity College of Music. But the commissioning process really got underway in 2010, and the ambition has been to encourage composers and musicians to write their own chorale preludes. Thus would be built up a corpus of works which amount to ‘a twenty-first century act of homage to Bach’, as Whitehead describes it. The idea has caught on, and already a considerable number have been written, and by some well-established and important composers.

The brief is to write in the composer’s own idiom (even if that includes an element of pastiche, a tradition of writing that has noble precedent). The piece should conform to Bach’s own approach to the book, so no longer than five minutes. But the style and scope is for the imagination of the composer. Even the ‘difficulty rating’, so to speak, is left open – ‘from beginner level to recital standard’. The goal is what Whitehead calls a Gesamtorgelbüchlein.

A head of steam built up quickly, as word travelled, and international festivals have been drawn into the Orgelbüchlein fold. New works have been given in the Spitalfields Winter Festival, the Carinthian Summer Music Festival, the Edinburgh Fringe, Toulouse les Orgues, the London Festival of Contemporary Church Music and New Paths, a new venture in East Yorkshire. The music writer David Nice, a scholar and critic whose work is always both elegant and forensically analytical, went to the Spitalfields concert, and had this to say:

Spanish composer Benet Casablancas and Lithuanian Justé Janulyté had sent the melodies underground, Casablancas’s wild fantasia – much the longest at just under the commission limit of five minutes – asking the organist to pull out a multitude of stops. Most interesting, perhaps, was the range of approaches: in addition to these mysteries and complexities, Thomas Daniel Schlee gave us a 21st century version of Bachian polyphony, Ēriks Ešenvalds contented himself with chaste homage to Bach and Jonas Jurkūnas’s reflection on the surprisingly cheerful Am Wasserflüssen Babylon burbled along cheerfully … in minimalist style.

The extent of this project is determinedly international. The role of cultural institutes and the European Commission itself has been at the heart of this. Whitehead says:

The European Commission representation in the UK has been tremendously helpful in opening doors to commissioning by various cultural bodies in London, most of whom are members of EUNIC. (These include the Dutch Embassy, the Austrian Cultural Forum, The Lithuanian Composers Union, the Latvian Embassy, the Czech Centre and the Instituto Cervantes). Composers from Latvia, Lithuania, Belgium, Czech Republic, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, Austria, France, the Netherlands and Spain have contributed to the growing international element of the project. The Festival Toulouse les Orgues has been a major collaborator in France. Some of the major European musical voices of our times have been engaged, including Louis Andriessen, Poul Ruders and Nico Muhly. The final collection will be a cross-section of the most interesting composition going on around Europe.

The search is now on for core funding to realize the project in its entirety.

In the fullness of time, the Gesamtorgelbüchlein will indeed be gesamt, complete. Then it will be recorded, if all goes to plan. This is a monumental project, worthy of success.

The quotations from great people extolling the virtues of J S Bach are legion; but there is also a rather gently witty story told of when the Voyager spacecraft were sent into outer space in the 1970s, with a cargo that included the music of Bach. Questioned about what music to send into space, the biologist and writer Lewis Thomas is reported to have said, ‘I would send the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach.’ Pause. ‘But that would be boasting.’

[1] Here is footage of Casals playing Bach http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VhcjeZ3o5us